An Imperial Guard Helmet of the Malagasy Kingdom from the reign of Queen Ranavalona III. This is the only known surviving example and it is in the Musee de l’Armee in Paris

The French invasion of Madagascar in 1897 ended the Malagasy Protectorate, but this brief war could also be the first time that forces on both sides worn sun helmets. It is just one part of a strange and somewhat fascinating story of the fall of the Merina Kingdom, two English adventurers and the annexation of the island nation.

The French presented the war as a conflict to extend its reach and influence over a savage people – and justified the establishment of a protectorate in 1882 based on treaties with the western coastal Sakalava people. The Malagsy Protectorate, which was in essence a French puppet, sought greater independence and rejected the claim of French protectorate status. The French military engaged Madagascar diplomatically, bombarded coastal cities and finally in January 1897 declared the entire island a French colony and violently quelled a brief rebellion. This brief war, which saw the end of any independence for Madagascar until after the Second World War, was also quite different from other conflicts in Africa.

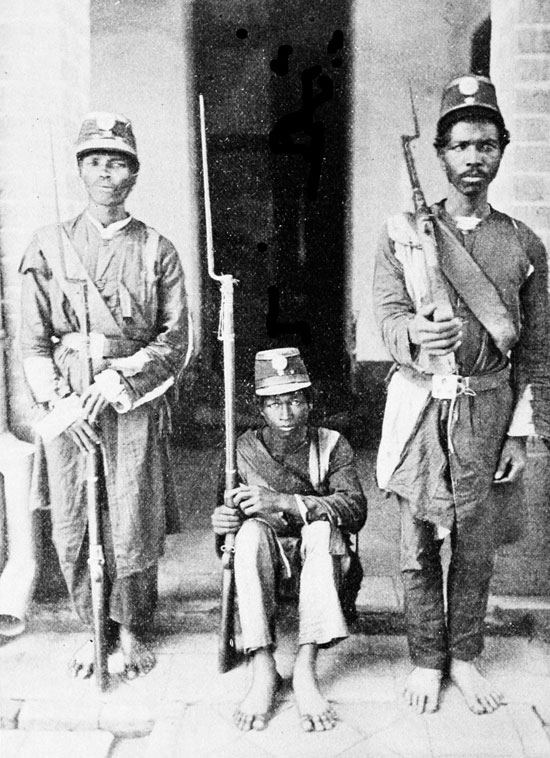

The Malagasy Army – despite the lack of shoes or boots – began to adopt a European look with modern rifles during the Malagsy Protectorate as a French puppet.

Whereas the traditional view is native arms in simple African garb the truth is that the war in Madagascar was closer to the Italian conflict against Ethiopia instead of the British invasion of Zululand. The army of the Merina Kingdom – the official government that ruled the island since 1540 and was the puppet government of the Malagsy Protectorate – was supplied by both the French and the British.

This included tropical sun helmets that featured a brass spike – something never utilized by the French on their respective sun helmets – along with an Imperial crown and eagle in a wreath badges. The crown is likely based on the Queen’s Crown used by the British military, and this makes sense give that the Malagasy Army was trained by two English “soldiers-of-fortune” General Digby Willoughby and Colonel Charles Robert St. Leger Shervinton. Both men had fought in South Africa in the Zulu and Basuto wars.

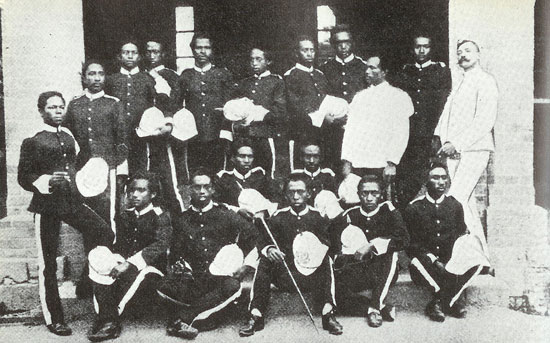

Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony of Madagascar inspects his troops circa 1890. These forces are equipped with French-made cavalry helmets. Their appearance is not that different from South American and even European armies of the day.

Willoughby not only helped train and organize the Malagasy Army, he even petitioned the British government to support the Merina Kingdom. However, because he was a British citizen it was decided by the Foreign Office that one of its nationals may not represent a foreign nation. He was arrested in London for his debt, and later court-martialed for malfeasance. After the French annexation of the island he went to Rhodesia and distinguished himself in the war against the Matabele – reportedly fighting for the tribal forces!

What is also notable is that under Willoughby and Shervinton the Malagasy Army adopted a modern European look that included not only sun helmets and French-influenced shakos but were organized along European lines with an officer corps. While neither Englishman actually took part in efforts to defend their adopted land from the French invaders, it is unlikely their presence would have made any difference – as the French sent some 14,000 men, 64 horses, 6,600 mules and more than a thousand carts. The French lost some 5,000 men in the conflict – many to disease – but the people of Madagascar lost their independence for another 60 years.

Colonel Shervinton (far right) with his native officers. Note these soldiers were outfitted in European style uniforms and colonial pattern sun helmets – the latter likely of French or English origin.

In many ways the French won in this last major land grab in Africa – apart from the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1936 – because of superior forces rather than superior technology, weapons and training. Just as the Ethiopians bested the Italians in 1896 when evenly matched in numbers with the Italians, it showed that the days of the Europeans having an upper hand in Africa were coming to an end. Modern military technology was reaching even the remotest parts of the dark continent and the days of imperialism were at an end.

I believe that Colonel Shervinton had a daughter Laura Kathleen Shervinton. She was our neighbour for many years in Kent, UK. Her home was a childs delight with many artefacts from her childhood growing up in Madagascar. I always remember her with fondness, a very noble lady. Rev.d Lorraine Apps Huggins.

This narration omits Colonel Graves, another British who trained the Malagasy army alongside Col. Shervington.