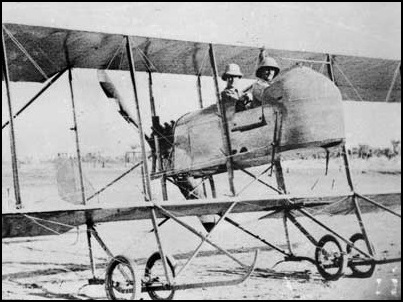

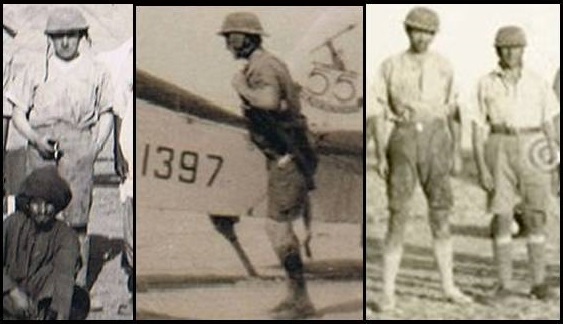

Figure 1. August 1918. The earliest close-up image found of the ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’, taken at the Royal Flying Corps/Royal Air Force, Flying School, Ismailia, Egypt, worn by Second Lieutenant Spaulding. This is the RFC 1917 Pattern, ‘Helmet, Cork Aviation’, externally the main shell is near identical to later versions, with puggaree, four side vents and a typical ‘sun helmet’ ventilation gap between the headband and shell. The outer covering at this time was made-up of four segments of cloth, a front and side seam can just be made out. A large rear brim can be seen shading the neck; however it has a very narrow and thin front peak, at this time these peaks were not part of the cork shell but were attached to the canvas cover. Soon, at least by mid-1919, the design was ‘revised’, adding a complete brim and extending the front peak slightly to help shade the face. After a 1926-27 review the liner and earflap fixings were also modified; it stayed in that configuration up to 1942. The ear-pockets can be seen to be holding large diameter gosport tube earpieces. (Image, see here).

Figure 1. August 1918. The earliest close-up image found of the ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’, taken at the Royal Flying Corps/Royal Air Force, Flying School, Ismailia, Egypt, worn by Second Lieutenant Spaulding. This is the RFC 1917 Pattern, ‘Helmet, Cork Aviation’, externally the main shell is near identical to later versions, with puggaree, four side vents and a typical ‘sun helmet’ ventilation gap between the headband and shell. The outer covering at this time was made-up of four segments of cloth, a front and side seam can just be made out. A large rear brim can be seen shading the neck; however it has a very narrow and thin front peak, at this time these peaks were not part of the cork shell but were attached to the canvas cover. Soon, at least by mid-1919, the design was ‘revised’, adding a complete brim and extending the front peak slightly to help shade the face. After a 1926-27 review the liner and earflap fixings were also modified; it stayed in that configuration up to 1942. The ear-pockets can be seen to be holding large diameter gosport tube earpieces. (Image, see here).

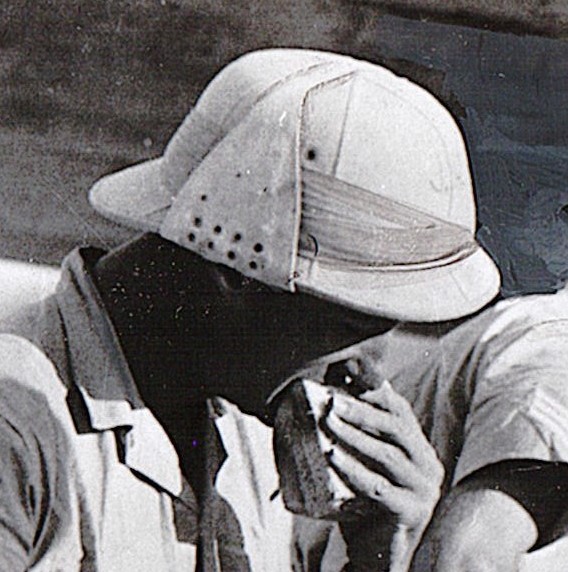

Figure 2. November 1940. Late production RAF ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’, only recently given the designation ‘Type-A’. A Bristol Blenheim crew takes refreshment at a desert airfield in North Africa, 27th Nov. 1940. The earflaps are done-up over the top of the helmet. Since c1919 the brim became part of the cork shell with the front peak getting wider through time, also details of the liner and earflaps were changed after a 1926-27 review. The cloth cover is now of six panels to save on waste during manufacture; but it is essentially the same helmet as the ‘1917 Pattern’ seen in Fig. 1. It maintained the same nomenclature ‘Helmet, Cork Aviation’ for 26 years and was 22C/13 for 23 of those years. It was finally made officially obsolete in 1942.

Figure 2. November 1940. Late production RAF ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’, only recently given the designation ‘Type-A’. A Bristol Blenheim crew takes refreshment at a desert airfield in North Africa, 27th Nov. 1940. The earflaps are done-up over the top of the helmet. Since c1919 the brim became part of the cork shell with the front peak getting wider through time, also details of the liner and earflaps were changed after a 1926-27 review. The cloth cover is now of six panels to save on waste during manufacture; but it is essentially the same helmet as the ‘1917 Pattern’ seen in Fig. 1. It maintained the same nomenclature ‘Helmet, Cork Aviation’ for 26 years and was 22C/13 for 23 of those years. It was finally made officially obsolete in 1942.

The RAF Cork Aviation Helmet is now rare, but in their time were standard kit and common in the tropical regions of the British Empire for which they were designed. Today they are often treated as just an interesting oddity, their origins shrouded in vague terms and there is confusion about their actual nomenclature. Using primary sources, however, they can be shown to have been one of the first, and longest-lived one piece RAF flying helmets; listed for a little more than a quarter of a century (1917 to 1942); (the ‘Type G’ 1963-93 was designed as a component part; an ‘inner’ to various fiberglass helmets). This also makes the RAF Cork Aviation Helmet an unusually long lived military sun helmet. During the interwar years the RAF was tasked to make ‘Colonial Policing’ its priority, as such 14 of the 19 RAF Squadrons in existence in the early 1920s were based in the tropics. Hence it was possibly issued to a majority of active flight crew and was worn on many of the RAF’s inter-war belligerent actions. They also seem to have been the progenitor of the 1930s/WWII/1950s South African military’s ‘polo’ helmet.

Figure 3. Early helmets, dated left to right 1919, 1920, 1924 and 1924, all have narrower front peaks than the post 1927 ‘Charles Owen’ type, but the brim looks to be a one piece solid structure, unlike the separate peaks seen on the original 1917 Pattern (see Figs. 1 & 6).

Figure 3. Early helmets, dated left to right 1919, 1920, 1924 and 1924, all have narrower front peaks than the post 1927 ‘Charles Owen’ type, but the brim looks to be a one piece solid structure, unlike the separate peaks seen on the original 1917 Pattern (see Figs. 1 & 6).

Figure 4. After a review of equipment in 1926-27, the 1917 design was found to be ‘satisfactory’ and new contracts were awarded primarily to Charles Owen & Co, and some others. The post 1927 ‘RAF, Cork Aviation helmet’ was basically the same design as earlier solid brim versions, but now all used Owen’s 1923 patented laced in liner (allowing easy attachment or removal of the earflaps), and the inside lining was in cotton, rather than silk, the outside cloth covering had six panels. The Charles Owen type helmets were supplied throughout the 1930s and into WWII.

Figure 4. After a review of equipment in 1926-27, the 1917 design was found to be ‘satisfactory’ and new contracts were awarded primarily to Charles Owen & Co, and some others. The post 1927 ‘RAF, Cork Aviation helmet’ was basically the same design as earlier solid brim versions, but now all used Owen’s 1923 patented laced in liner (allowing easy attachment or removal of the earflaps), and the inside lining was in cotton, rather than silk, the outside cloth covering had six panels. The Charles Owen type helmets were supplied throughout the 1930s and into WWII.

Figure 5. Mesopotamia, 1915. Urgent requests for scouting aircraft were sent by General Barrett in January 1915, only two had arrived by May; but with occasional additions the first under strength RFC Flight in the Middle East was in existence by the end of that year. In the tropics conventional wisdom about the detrimental effects of ‘actinic rays’ made the wearing of sun helmets in exposed cockpits inevitable. Here crew in a Maurice Farman wear Cawnpore and Wolseley sun helmets. Neither were suitable, especially with increasing speeds as newer aircraft came into service. The typical close-fitting leather caps then standard in Europe were also impractical for use in extremely hot areas. With long distance reconnaissance over the scorching deserts likely to increase it seems that in 1917 the newly formed ‘HQ Royal Flying Corps Middle East’ decided to acquire a specialized tropical flying helmet; at least two prototypes may have been trialed (see Fig. 12)

By 1917, the ‘Middle East Brigade-RFC’ included units based in Macedonia, Mesopotamia, Palestine, East Africa; and soon Trans-Jordan, with flight schools in Egypt. Because of the climate in these areas the standard bulky thermally insulated ‘Home’ and ‘Western Front’ equipment was considered inappropriate, especially during the summer months, so dedicated tropical equipment was developed. Collectively references to, and deployments in these parts tended to be termed ‘Middle East’ (with definite geographic bounds) and/or ‘East of Suez’ (a changing geopolitical term). At some point, however, the cork aviation helmet has picked up the epithet ‘East of Malta’. It appears to be the only item thus labeled and the terminology does not seem to exist elsewhere as either an official or colloquial term; as such, the origins of the phrase ‘East of Malta’ is obscure and may not be an actual period designation. After WWI the RAF was mandated to concentrate on ‘Colonial Policing’ with a European war seen as unlikely for at least ten years, hence the cork aviation helmet was a stock piece of equipment for the RAF’s main role in the early interwar period. Images from this period show the helmet in use over a vast geographic range (Figs. 11 to 30).

It appears that ‘Middle East & East of Suez’ pilots were issued with both the soft cap (22C/5) style leather helmet and the cork aviation helmet (22C/13) and were usually at liberty to wear either, depending on the amount of sun; leading to the cork helmet having the further appellation of ‘summer wear’ or ‘summer dress’. Several images exist of pilot and observer using both in a single aircraft, or carrying both helmet types to their aircraft. Prodger (1995) on page 183 shows a “Khaki Cotton helmet with Gosport receivers, custom made for an RAF pilot stationed in India, 1937 to wear under his type “A” flying helmet.”

The earliest evidence of a purposely designed military flying sun helmet is in the Imperial War Museum, RAF Duxford, where an example attributed to the Royal Flying Corps in 1917, is catalogued as ‘Helmet, Cork Aviation RFC Pattern 1917’. In the collection it is UNI 177; – Uniforms and Insignia, objects originating from within the WD, i.e. it is not a later donated ‘historical curio’ but a contemporary evaluation piece or type example or ‘pattern’. This example was produced by Hobson & Sons and is described by the IWM as ‘helmet khaki cloth covered tropical flying helmet, with khaki pagri band, four vent holes either side. Cloth earflaps and brass buckle fastening. The lining is in red silk and sweat band in fine leather’. Apart from the silk lining this same description could be used for examples dated right up to 1942.

The earliest period images (Figs. 1, 6 & 12) would indicate that the first examples had a very narrow front brim, but a wide rear brim as in later examples. Looking at the blue-prints in Fig. 6 it appears it was based on a simple cork dome shell, with the front and rear peaks as separate parts attached to the cloth cover. The early post-WWI helmets shown in Fig. 3, indicate that it received a revision to the brim quite early on, making it one piece and slightly extending the front peak. As a sun helmet it always had a pronounced ventilation gap between the headband and shell initially accomplished with typical cork spacers before 1927 and after that date with a suspended laced in liner.

It appears that both the original 1917 Pattern cork helmet and the early solid brim versions were issued until 1926-27. At the time of the Armistice the RAF had a fully kitted 30,000 pilots plus observers; by the end of 1919 there were only 6,000; so with at least 24,000 sets of spare clothing, continued manufacture, or the development of new types was not an immediate priority. Making do with surplus WWI equipment was the norm post-war. After these ‘Lean Years’, however, the aging WWI equipment started to be re-evaluated by the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE). In a 1926-27 review the ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’ was found to be ‘satisfactory’ and with some revisions new production seems to have commenced in the late 1920s or early 30s.

The new production seems to have been mainly by Charles Owen & Co, London taking advantage of their 1923 ‘Royal Letters Patent 207475’sweatband, a laced-in liner, which made installing and removing the earflaps simple. Early ‘Charles Owen’ helmets appear to have no labeling on the liner, but later production had the trade mark ‘Comfortilet’ embossed into the leather sweatband. The new production included the ~1 ½ inch extension of the front peak and possibly a flattening of the rear peak’s downward dip. Rarely helmets produced by others, including Hobson & Sons and later Helmets Ltd, do appear, but still using the Charles Owen & Co patent liner type. On these post 1927 helmets the lining material bonded to the inside of the shell is cotton, green under the brim and natural cotton in the dome. Due to the helmets intended use the puggaree was securely pinned with at least 10 pins, a minimum of 2 pins in every coil, located in the folds at front and back, to stop it unraveling in the slipstream.

Developments and Modifications

Early on there is a lack of surviving documentation, this situation improves after 1920 with equipment lists and a number of other documents existing regarding the Cork Aviation Helmet including ‘Air Ministry Weekly Orders (A.M.W.Os.) and Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) reports such as : –

In 1925— A.M.W.O. 583222/25. 568.— ‘Fur-Lined Caps and Cork Aviation Helmets—Alteration to prevent Loss of Goggles.’

- To minimise the risk of loss of goggles during a flight, the fitting of a strap and buckle, as shown in the outline sketches below, to backs of “Caps, fur-lined,” reference No. 5, and to “Helmets, cork, aviation,” reference No. 13, Section 22c, Air Publication 1086, has been approved.

- The modification is to be incorporated in all fur-lined caps and cork aviation helmets in possession of officers and units, and is to be carried out locally.

- The following instructions are issued for guidance in fixing the strap and buckle :—

(i) …—(a) A leather strap ½-in. wide, fitted with a ½-in. one-prong buckle, ….etc.

(b) A strap, 2-in. long ….so as to form a loop 7/8-in. wide when the buckle is fastened.

(ii) Cork aviation helmets. —The straps and buckle are to be fitted in the centre of the under side of the back peak of the cork aviation helmet in a similar manner to that employed on fur-lined caps.

(iii) The sewings are to be of “silk, MC., drab, No. 18,” reference No. 151, Section 22A.

- Bills for straps and buckles purchased locally are to be paid….etc.

- All future issues of fur-lined caps and cork aviation helmets will have this modification incorporated prior to issue.

At the time this document was issued 22c/5 (Fur-Lined Cap) and 22c/13 (Cork Aviation Helmet) were the only flying headwear being officially issued by the RAF. 22c/12 (Helmet, Aviation), a training crash helmet, was still available but had been declared ‘Obsolescent’ in 1924 and was being phased out (Link to Warren piece).

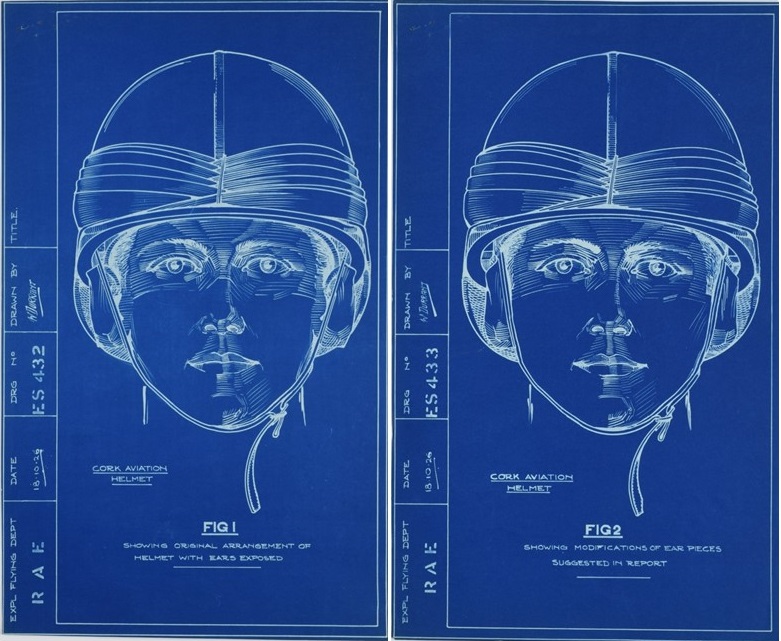

After perhaps nine years in service, on 14 August 1926 a sample of the Cork Aviation Helmet arrived at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) for a scientific re-evaluation. Across the board WWI designed kit was still being used at this time due to the surfeit of gear at the time of the Armistice; as the financial situation improved it was thought re-equipping might be prudent if anything was found to be outdated. A physical inspection lead to Royal Aircraft Establishment Report No. K.2186. ‘Report on cork aviation helmet’ dated 18 October 1926. The conclusions of the short report read : –

‘As may be seen from FIG.1 the arrangement of the ear pieces is such that they leave the ears partially exposed and they actually act as deflectors to throw the draught into the ear. This would be extremely uncomfortable in use and it is therefore suggested that a modification be made in the manner shown in Fig.2. In this sketch the upper attachment of the ear piece is shown on the inside of the inner band of the helmet, instead of being attached to the body of the helmet as in Fig.1. With this modification, it is considered that the helmet would be suitable for service use as it is, in other respects, satisfactory.’

Figure 6. FIG 1 & 2 from ‘Report on Cork Aviation Helmet’, RAE Report No.K.2186, 18 Oct. 1926, showing a 1917 Pattern version. Blueprints showing a front view of a helmet so the upper part of the earflaps can be seen. At left the standard helmet as in 1917-1926, the earflaps are attached to the shell, this allowed air to flow into the ear pocket. At right it was suggested the simple expedient of attaching the flap to the liner rather than the shell would produce a closer fit. It can be seen here that the liner at this date has cork spacers (shown as dark blue blocks at top of the flaps in ‘FIG.2’). The single join shown in the outer cotton covering would indicate it has only four panels and the way the rear peak comes in close at the sides and the very small front peak attached to the cover over a simple dome shaped thick cork shell, shows this is the 1917 Pattern version (compare it with Fig. 1), possibly old wartime stock.

Figure 6. FIG 1 & 2 from ‘Report on Cork Aviation Helmet’, RAE Report No.K.2186, 18 Oct. 1926, showing a 1917 Pattern version. Blueprints showing a front view of a helmet so the upper part of the earflaps can be seen. At left the standard helmet as in 1917-1926, the earflaps are attached to the shell, this allowed air to flow into the ear pocket. At right it was suggested the simple expedient of attaching the flap to the liner rather than the shell would produce a closer fit. It can be seen here that the liner at this date has cork spacers (shown as dark blue blocks at top of the flaps in ‘FIG.2’). The single join shown in the outer cotton covering would indicate it has only four panels and the way the rear peak comes in close at the sides and the very small front peak attached to the cover over a simple dome shaped thick cork shell, shows this is the 1917 Pattern version (compare it with Fig. 1), possibly old wartime stock.

A helmet with the 1926 recommended modifications was returned for testing to the Royal Aircraft Establishment in mid-1927. After exhaustive flight tests in a D.H.9A, fitted with short exhaust pipes, a further report was produced ‘Report on cork aviation helmet’, RAE Report No.K.2278, 30 Sep. 1927. It was found that the helmet with the 1926 alterations was “quite satisfactory from the point of view of reception and noise exclusion; the earphone attachment harness was also found to be comfortable.”

This second report did however recommend that the chinstrap be widened and the rear peak altered: –

“(i) The Tape used to strap the helmet under the chin is too narrow for the fastener and therefore takes the form of a small string at one corner of the fastener. It is suggested that a wider and more robust strap could be used to advantage and would give additional comfort to the wearer.”

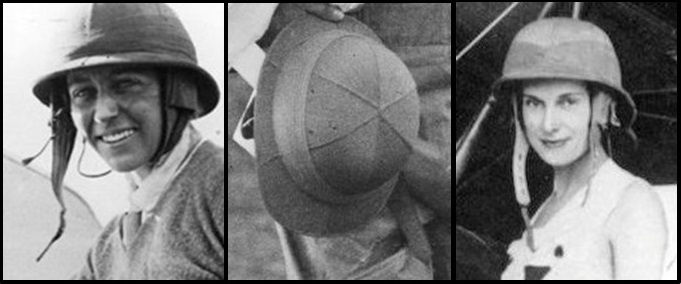

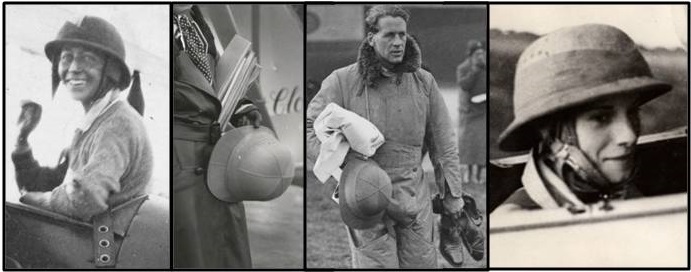

Figure 7. Strap Modifications. Left, Amy Johnson image date May 1930, shows a thin strap as mentioned in the RAE report, which has rucked-up in the corner of the buckle forming a ‘string’ after prolonged use. Middle, Lord Clydesdale, image date Feb. 1933, a much thicker strap can be seen to the bottom right of the helmet. Right, Jean Batten Oct. 1936, shows a chinstrap with wide inner cover. These images are evidence that at least some heeded the 1927 RAE recommendation. Note these are all celebrity aviators; rank and file RAF pilots did not seem to pose for detailed portraits in flight gear. Lord Clydesdale’s helmet at centre is probably a private purchase item, notice it only has two vent holes. All have the encircling brim shape introduced by mid-1919.

Figure 7. Strap Modifications. Left, Amy Johnson image date May 1930, shows a thin strap as mentioned in the RAE report, which has rucked-up in the corner of the buckle forming a ‘string’ after prolonged use. Middle, Lord Clydesdale, image date Feb. 1933, a much thicker strap can be seen to the bottom right of the helmet. Right, Jean Batten Oct. 1936, shows a chinstrap with wide inner cover. These images are evidence that at least some heeded the 1927 RAE recommendation. Note these are all celebrity aviators; rank and file RAF pilots did not seem to pose for detailed portraits in flight gear. Lord Clydesdale’s helmet at centre is probably a private purchase item, notice it only has two vent holes. All have the encircling brim shape introduced by mid-1919.

“(ii) The back peak of the helmet catches the wind badly and owing to its angle relative to the slipstream tends to be lifted off the head. It is also pointed out that when used in aircraft of the D.H. 9A type where the backs of the seats are high, the peak fouls the back and is a source of annoyance (see Fig. 21). It is suggested that the peak should be made to fit the neck more closely.”

It is possible this paragraph lead to the another re-working of the brim, the width of the front peak may have been increased slightly and the rear peak’s angle may have been made flatter, rather than fitting ‘the neck more closely’. Photographic evidence, however, is ambiguous as to the scale of these changes at this time. In addition to the recommendations about the rear peak, the mode of goggle attachment was questioned:-

‘(iii) Some definite scheme should be introduced to enable the goggles to be attached to the side of the helmet or ear flaps without having to remove the helmet. Goggles if worn on the ground or when running up the engine tend to mist badly, and the removal of the helmet under such conditions is both inconvenient and from a medical point of view, undesirable. Although it is realized that a number of schemes could be produced to suit particular requirements it is suggested that in view of the regulations regarding the loss of goggles, this is undesirable. It is therefore suggested that if this helmet is to be used on Service, instructions similar to those contained in Air Ministry Weekly Order No. 568/25 be issued.”

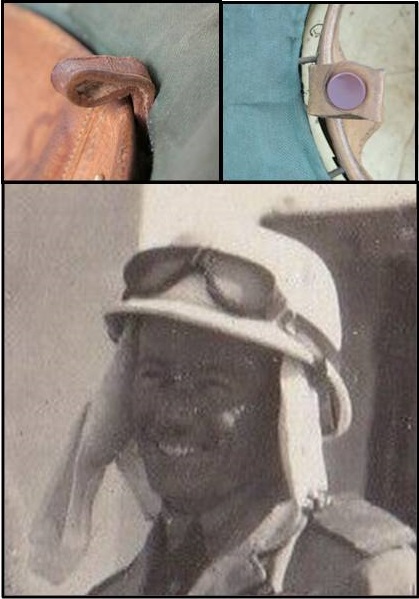

This paragraph would seem to imply the helmet with the modified earflaps which was sent to RAE for re-evaluation did not have the modifications recommended in the 1925 A.M.W.O. 568 (see above). In surviving examples, which are available for study, none seem to have the buckle modification mentioned in A.M.W.O. 568. Existing goggle retaining straps usually seem to be factory attached leather loops on the back of the helmet liner, some having a closed loop, others can be opened via a snap connector. These loops were probably introduced into factory production after the 1925 A.M.W.O. 568; with instruction (5) stipulating that goggle retaining loops would from then on be standard on subsequently issued helmets. These small loops were probably a practical and simpler measure than the buckle and perforated tongue straps suggested. The loop enabled the main goggle strap to go externally around the helmet, but be secured by a secondary strap passing under the rear of the helmet and through the loop (Fig. 8, Bot. & Fig. 22 Cent.). Or the goggle strap was threaded through the loop directly and worn around the head, under the helmet. This enabled the goggles to be pulled down to the chin whilst ‘running up’ etc., without them slipping down the neck (see Fig.30, right).

Documentary evidence (e.g. Figures 1 & 12 and the IWM 1917 example) shows the helmet had been in service for almost a decade by this time, so the reference ‘if the helmet is to be used on service’ relates to its continued use and the possibility of new production.

Figure 8. On most existing helmets the small loop between the back of the liner and the shell seem to be factory made. At top left a solid loop, at top right a loop which can be opened via a snap fastener. The closed loop retainer could only be used with a two-piece goggle strap with a hook fastener, or a subsidiary strap (e.g. photo at Bot.). The snap fastener allowed single loop goggle straps to be directly attached to the helmet. Some helmets do not have such a loop; they were relatively weakly attached however, by a single split rivet into the fiber backing ring of the sweatband, so they may have broken away. (Top images from ‘The Historic Flying Clothing Company’). Bottom image, shows a pilot in Egypt, in 1929, his earflaps appear to be covered in white cotton extending to the back as a Havelock, his Triplex ‘Featherweight’ goggles are secured by two straps, the main elastic one goes externally around the helmet, and a second thinner leather strap attaches to a ring on the original strap’s sliders and then passes under the rear of the helmet, probably passing through the retaining loop.

Figure 8. On most existing helmets the small loop between the back of the liner and the shell seem to be factory made. At top left a solid loop, at top right a loop which can be opened via a snap fastener. The closed loop retainer could only be used with a two-piece goggle strap with a hook fastener, or a subsidiary strap (e.g. photo at Bot.). The snap fastener allowed single loop goggle straps to be directly attached to the helmet. Some helmets do not have such a loop; they were relatively weakly attached however, by a single split rivet into the fiber backing ring of the sweatband, so they may have broken away. (Top images from ‘The Historic Flying Clothing Company’). Bottom image, shows a pilot in Egypt, in 1929, his earflaps appear to be covered in white cotton extending to the back as a Havelock, his Triplex ‘Featherweight’ goggles are secured by two straps, the main elastic one goes externally around the helmet, and a second thinner leather strap attaches to a ring on the original strap’s sliders and then passes under the rear of the helmet, probably passing through the retaining loop.

Flying Clothing Nomenclature

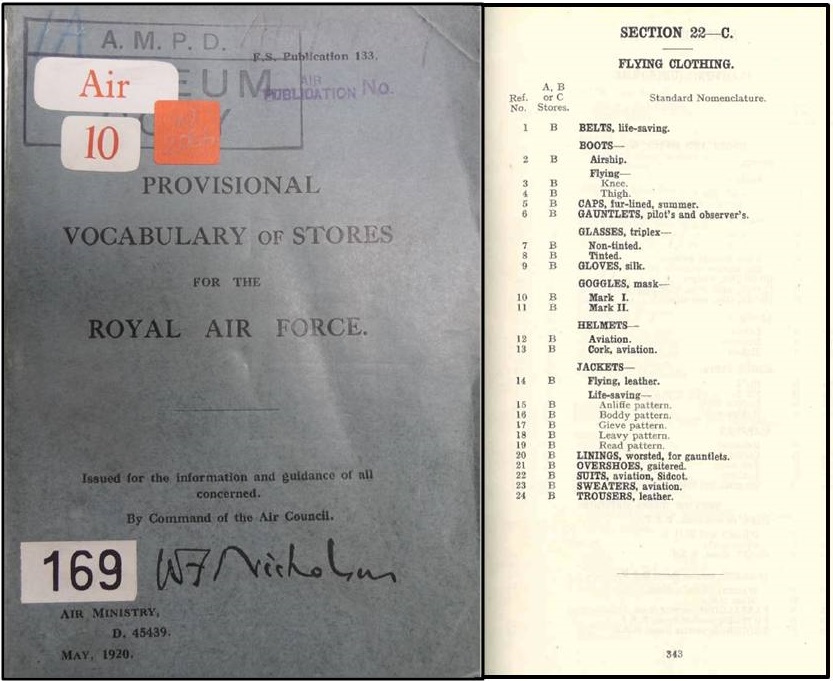

Before the creation of the RAF the problem of integrating the RFC accounting system with that used by the RNAS was tackled. This work led to the development of a standardized nomenclature and the emergence of the first incomplete RAF Vocabularies during late 1917 and 1918 (O’Hara, 2005 & Stone, 2017). Rood (2014) shows a 1918 British Air Board list, and a priced list of standard issue clothing for aviators, (crew were liable for lost or damaged kit). The particular lists Rood cites were distributed via ‘Air Board Weekly Orders’ 5th December 1918, (AMWO 1577/18) and his second, a priced list is AMWO 19/19, 2nd January 1919, they seem to concern Western Front clothing and were soon to make up roughly the first ten items of the 22C Section (Flying Clothing) of the original F.S. (A.P.) 133 ‘Provisional Vocabulary of Stores for the RAF’ officially published May 1920 (see Fig. 9). ‘Helmet, Cork, Aviation’ 22C/13 appears in the earliest surviving lists (F.S. 133, May 1920) and with its 1917 date in the IWM collections, and images of it in use during 1918 it can safely be assumed that it appeared on equipment lists meant for tropical areas from the earliest RAF days.

Figure 9. Thought to be the first and only edition of F.S.133, (May 1920) ‘Provisional Vocabulary of Stores for the Royal Air Force’. Cover and page 343, the 22-C section, ‘Flying Clothing’. Here the list is alphabetically ordered in clothing type, with reference numbering actually in sequence. This is possibly the list as it appeared when compiled at the setting-up of the RAF in 1918. The ‘Helmet-Cork, aviation’ appears as the 13th item of listed clothing due to its 1917/18 original issue date.

Figure 9. Thought to be the first and only edition of F.S.133, (May 1920) ‘Provisional Vocabulary of Stores for the Royal Air Force’. Cover and page 343, the 22-C section, ‘Flying Clothing’. Here the list is alphabetically ordered in clothing type, with reference numbering actually in sequence. This is possibly the list as it appeared when compiled at the setting-up of the RAF in 1918. The ‘Helmet-Cork, aviation’ appears as the 13th item of listed clothing due to its 1917/18 original issue date.

At amalgamation a new RAF ‘Vocabulary’ was produced and the ‘RFC Pattern 1917’ part was dropped, it becoming simply ‘Helmet, Cork Aviation’. Throughout its life it was always referred to as the ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’, but for administration purposes it was sometimes given various alphanumeric references. The initial RFC design and 1917 date helps to explain the type’s very low RAF ‘Vocabulary’ Reference Number 22C/13 in F.S. 133 and low Code Word (SDYBI) in Air Publication 809. In the Imperial War Museum collections, set-up in 1917, as mentioned the ‘Helmet, Cork Aviation’ appears as the 177th item of their ‘Uniforms and Insignia’ section, a relatively low number (as it includes Navy, Army and Air Force items), and places it well within the WWI period of museum procurements. Very tentatively it may possibly have had the Sealed Pattern No. 10166, as this appears on the museum specimen in red wax, this is in the right number range for a 1917 item, but at present there is no way to confirm this.

In the 1926 and 1927 RAE reports mentioned earlier the helmet type is exclusively referred to as the ‘cork aviation helmet’, with no alphanumeric type or reference numbers mentioned what-so-ever. The A.M.W.Os., typically use just the name ‘Cork aviation helmet’, with the long winded ‘“Helmets, cork, aviation,” reference No. 13, Section 22c, Air Publication 1086’, apparently only being used to steer the quartermaster to the stores needing modification, rather than being used as a commonly used designation. The revisions did not lead to any change in nomenclature, as it was essentially the same helmet.

Figure 10. Left 3 examples of labels in Charles Owen produced Cork Aviation Helmets. It seems early production helmets had a paper label, this is almost always worn off. At left a factory applied paper label (1936) with a separate A.M. acceptance stamp (properly called an ‘Air Ministry Property Mark’). It seems later helmets (two center images 1939 and 1940) were factory stamped, with details and ‘A.M. Property Marks’. At top right, later manufacture of Charles Owen & Co, London with their ‘Comfortilet’ liner, with its 1923 patent number embossed in the leather. At right bottom a late ‘Hobson & Sons’ helmet, but with a Owens’ patent pattern liner. (First 4 images from ‘The Historic Flying Clothing Company’)

Figure 10. Left 3 examples of labels in Charles Owen produced Cork Aviation Helmets. It seems early production helmets had a paper label, this is almost always worn off. At left a factory applied paper label (1936) with a separate A.M. acceptance stamp (properly called an ‘Air Ministry Property Mark’). It seems later helmets (two center images 1939 and 1940) were factory stamped, with details and ‘A.M. Property Marks’. At top right, later manufacture of Charles Owen & Co, London with their ‘Comfortilet’ liner, with its 1923 patent number embossed in the leather. At right bottom a late ‘Hobson & Sons’ helmet, but with a Owens’ patent pattern liner. (First 4 images from ‘The Historic Flying Clothing Company’)

The helmet’s nomenclature remained as ‘Cork Aviation Helmet- 22c/13’, until early WWII when the ‘Air Publication 1086’ listing was again updated and rationalized due to the massive mobilization and re-equipping occurring with the outbreak of war. The type receiving the additional stores reference sequence 22c/274-284, denoting 11 different sizes, indicating it was still, and was expected to remain a regularly issued item. Although still know by all as the ‘cork aviation helmet’ it was probably at this time that it was retrospectively given the designation ‘Type A’ to distinguishing it from the ‘Type B’ flying helmet (22c/65), which had been introduced in the mid-1930s; these were the only two RAF flying helmet types current at the start of the Second World War. This retrospective assigning of a type ‘A’ designation to an existing item when it was to continue alongside a subsequent or similar item was standard RAF practice (e.g. Air Ministry Order, A207/1936, which deals with fitting new telephone receivers to flying caps, says about the earlier receivers ‘these will in future be known as Type A’). It was during the 1930s that the differentiation between soft flying ‘caps’ and ‘helmets’ disappeared and all became flying or aviation ‘helmets’, this may have been to counter confusion with the numerous (at least 13) non-flying ‘cap’ types listed under Sections 22A to H Clothing & Accoutrements – ‘Uniforms’, ‘Necessaries’ and ‘Miscellaneous’. All other RAF flying helmets had by WWII been classed as obsolete and hence were never given retrospective alphanumeric type designations (although the ‘fur-lined cap’ 22c/5, may have acquired the ‘MkI’ designation when the ‘1930 Pattern’ (22c/51) was introduced, as there appears to be no reference to a MkI flying helmets pre-‘1930 Pattern’s’ late 1920s development).

Often helmets also have an A.I.D. (Aeronautical Inspection Directorate) stamp under the liner, these were unique stamps identifying the A.I.D. staff member who inspected the item and declared it fit to be issued (i.e. no dates or other item information is hidden in the A.I.D. code).

In summary; – throughout its ~26 year life it was generally referred to as the ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’, but for administration purposes it was sometimes given various alphanumeric references. It was sometimes also referred to as ‘summer wear’ or ‘summer Dress’ due to crew having the choice to wear it or the standard ‘Fur-lined cap’ during their tropical postings, depending on the weather. From 1920 to 1942 it had the Section/Reference Number ‘22C/13’ and from 1921 to 1924 it had the code word ‘SDYBI’. These Reference Numbers and code words were used purely for administration and were not in day to day usage, even in official communications, where ‘Cork Aviation/flying Helmet’ was invariably preferred. At the start of WWII rationalization of the equipment lists took place, the Cork Aviation/Flying Helmet received the additional 22C number range of 274-284 denoting the sizes available. It was only at this late stage in its life that it was retrospectively given the ‘Type-A’ designation to distinguish it from the soft ‘Type-B’ helmet; the only other flying helmet type still on the RAF books at that time.

Operational Use

The IWM example and images of its First World War use indicates the helmet was designed, issued and used during WWI. However, the type’s hay-day was following WWI when Britain was reasserting itself in neglected parts of the Empire and trying to establish its authority in former Ottoman Empire areas she had been mandated to administer by the League of Nations. The RAF was directed by the Government to concentrate on ‘Colonial Policing’ in this period, with the majority of physical and operational resources going toward this goal. Preparations and planning for a ‘European War’ were in abeyance and remained so until the early 1930s. Routine Policing of these ‘Middle East & East of Suez’ areas in the inter-war years mean these helmets appear in images from across the Middle East and elsewhere (Figures 11 to 29). Today these routine deployments are mostly forgotten and images of the helmet in use are not easily accessible, so shown here is a selection of images illustrating the type’s geographic range and longevity.

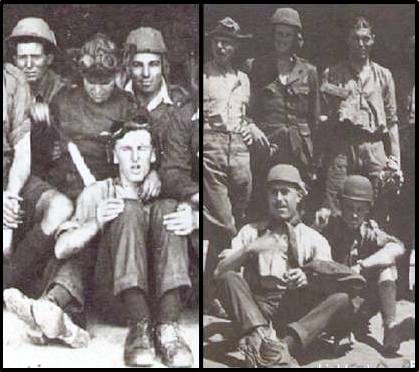

Figure 12. The earliest images found of Cork Aviation Helmets in use during WWI, Ismailia, Egypt, 1918. Left, June, 1918, right, July, 1918. The most unambiguous examples are those on the two seated airmen at right. These are identical to the helmet shown in Figure 1, the ear flaps are done-up over the top of the helmets. Sun catches the brim of the seated airman at right and shows there is a very narrow peak. The helmets worn in the back rows, however are similar aviation helmets with earflaps, but more ‘flower-pot’ like; whether these are just a variation of the ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’, or a different model, or prototype is not known (perhaps IWM UNI. 175, ‘Flying Helmet, Cork, Round’?). (Details from images on Brian Johannesson’s collection, see here).

Figure 12. The earliest images found of Cork Aviation Helmets in use during WWI, Ismailia, Egypt, 1918. Left, June, 1918, right, July, 1918. The most unambiguous examples are those on the two seated airmen at right. These are identical to the helmet shown in Figure 1, the ear flaps are done-up over the top of the helmets. Sun catches the brim of the seated airman at right and shows there is a very narrow peak. The helmets worn in the back rows, however are similar aviation helmets with earflaps, but more ‘flower-pot’ like; whether these are just a variation of the ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’, or a different model, or prototype is not known (perhaps IWM UNI. 175, ‘Flying Helmet, Cork, Round’?). (Details from images on Brian Johannesson’s collection, see here).

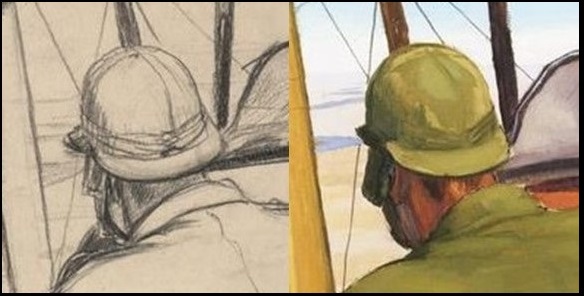

Figure 13. July 1919, BE2C pilot, approaching Hit, Mesopotamia. Details of Sydney Carline’s sketch and completed water colour showing the Cork Aviation Helmet. The narrow front brim, with wider rear is clear as is the puggaree and the earflaps with pockets for communication earpieces. The four outer cloth panels are recorded. (Details from IWM’s cat. no. ‘Art.IWM ART 4617’).

Figure 13. July 1919, BE2C pilot, approaching Hit, Mesopotamia. Details of Sydney Carline’s sketch and completed water colour showing the Cork Aviation Helmet. The narrow front brim, with wider rear is clear as is the puggaree and the earflaps with pockets for communication earpieces. The four outer cloth panels are recorded. (Details from IWM’s cat. no. ‘Art.IWM ART 4617’).

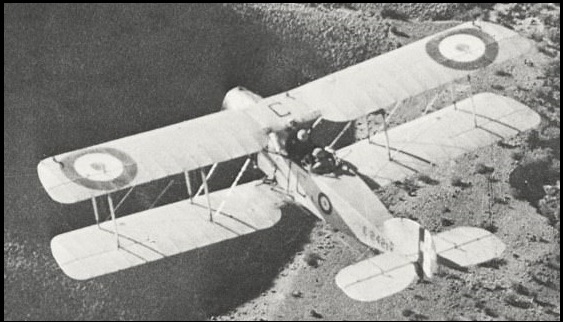

Figure 14. Photographs of Cork Aviation Helmets being worn in DH4A’s in Mesopotamia 1919.

Figure 15. 15th December 1919. FE2b Bristol Fighter in Palestine. Here the front brim, or peak, seems to be wider, if the published image date is correct this means the Cork Aviation Helmet pattern had received a revision before this date.

Figure 15. 15th December 1919. FE2b Bristol Fighter in Palestine. Here the front brim, or peak, seems to be wider, if the published image date is correct this means the Cork Aviation Helmet pattern had received a revision before this date.

Figure 16. A Bristol F2b Fighter in Afghanistan 1919-1920. Both pilot and navigator are wearing narrow peaked cork helmets, which seem to have darker tonal values than that expected from normal khaki.

Figure 16. A Bristol F2b Fighter in Afghanistan 1919-1920. Both pilot and navigator are wearing narrow peaked cork helmets, which seem to have darker tonal values than that expected from normal khaki.

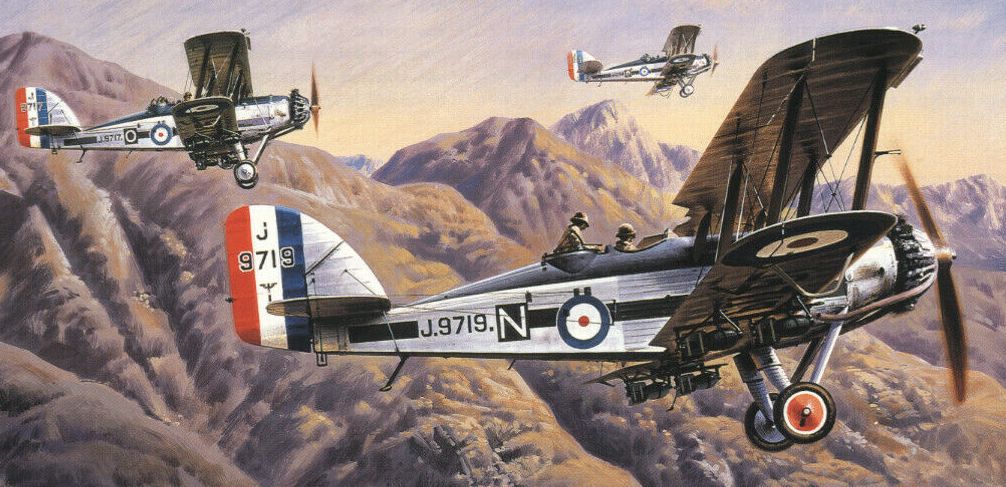

Figure 17. Again in Afghanistan, 1925, during ‘Pinks War’ a Bristol F2b returning from a raid on Jelal Khel.

Figure 17. Again in Afghanistan, 1925, during ‘Pinks War’ a Bristol F2b returning from a raid on Jelal Khel.

Figure18. Still wearing cork helmets in Afghanistan fifteen years on from Fig. 16; 1934, No. 2 Squadron on patrol over the Khyber Pass in Hawker Harts.

Figure18. Still wearing cork helmets in Afghanistan fifteen years on from Fig. 16; 1934, No. 2 Squadron on patrol over the Khyber Pass in Hawker Harts.

Figure 19. View up the bombsight of a Hawker Hart in Afghanistan, 1932, during the Shamozai bombings. The cork aviation helmet’s strap is undone and hangs at left; he is wearing standard RAF Mk II ‘Lightweight’ goggles.

Figure 19. View up the bombsight of a Hawker Hart in Afghanistan, 1932, during the Shamozai bombings. The cork aviation helmet’s strap is undone and hangs at left; he is wearing standard RAF Mk II ‘Lightweight’ goggles.

Figure 20. A late DH9A of ‘27’ Squadron over Karachi, about 1930, again a darker coloured helmet. It seems to be an old narrow peak example. Its potential interaction with the head rest as mentioned in the 1927 RAE Report K.2278 can be seen.

Figure 20. A late DH9A of ‘27’ Squadron over Karachi, about 1930, again a darker coloured helmet. It seems to be an old narrow peak example. Its potential interaction with the head rest as mentioned in the 1927 RAE Report K.2278 can be seen.

Figure 21. Datable images in Iraq. Left 1924, illustrates that one crew member of a DH9A wears a narrow peaked cork aviation helmet whilst the other dons a fur-lined cap. Centre, 1924, right, 1926.

Figure 21. Datable images in Iraq. Left 1924, illustrates that one crew member of a DH9A wears a narrow peaked cork aviation helmet whilst the other dons a fur-lined cap. Centre, 1924, right, 1926.

Figure 22. RAF in Egypt, 1920s. Left, 216 (B) SQN, Vickers Vimy pilot viewed through ‘Brass’, 1926. Middle Top, Heliopolis, 1929, the pilot has sunglasses and goggles, the arrangement of main goggle strap around a post 1927 Pattern helmet and a secondary strap passing under the rear peak can be made out. Middle Bot. Another wide peaked helmet at a desert landing field, 1928. Right, 1927, an earlier helmet on a pilot visiting the ‘Great Bitter Lake’.

Figure 22. RAF in Egypt, 1920s. Left, 216 (B) SQN, Vickers Vimy pilot viewed through ‘Brass’, 1926. Middle Top, Heliopolis, 1929, the pilot has sunglasses and goggles, the arrangement of main goggle strap around a post 1927 Pattern helmet and a secondary strap passing under the rear peak can be made out. Middle Bot. Another wide peaked helmet at a desert landing field, 1928. Right, 1927, an earlier helmet on a pilot visiting the ‘Great Bitter Lake’.

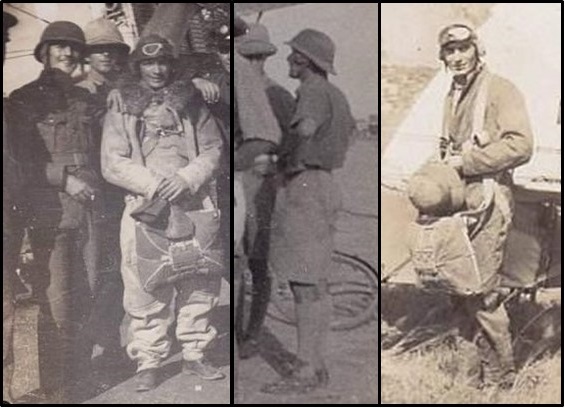

Figure 23. ‘27’ Squadron, B Flight, in India 1929. Aviators with Cork Aviation Helmets. These images illustrate that aviators were free to use the cork helmet or skullcap type as they saw fit. Note the colour tone of the cork aviation helmet at left against the Wolseley behind it.

Figure 23. ‘27’ Squadron, B Flight, in India 1929. Aviators with Cork Aviation Helmets. These images illustrate that aviators were free to use the cork helmet or skullcap type as they saw fit. Note the colour tone of the cork aviation helmet at left against the Wolseley behind it.

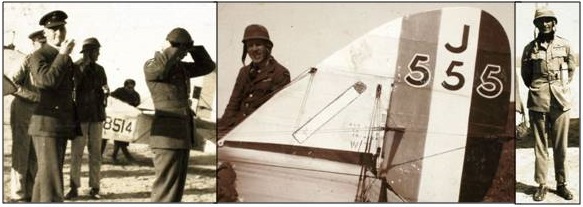

Figure 24. Left two, ‘55’ Bomber Squadron, RAF Hinaidi, Iraq, 1930-37. Right, Aircrew, Iraq, 1928. Standard flying gear appeared to be short sleeved flannel shirts (cut-down 22B/31-32?), shorts (22D/45, Overseas, shorts khaki drill), ankle boots (22D/2) or canvas shoes (No. 1-4) and long woollen (Worsted) socks (22B/55), the latter almost as symbolic of the British Empire as the sun helmet itself!

Figure 24. Left two, ‘55’ Bomber Squadron, RAF Hinaidi, Iraq, 1930-37. Right, Aircrew, Iraq, 1928. Standard flying gear appeared to be short sleeved flannel shirts (cut-down 22B/31-32?), shorts (22D/45, Overseas, shorts khaki drill), ankle boots (22D/2) or canvas shoes (No. 1-4) and long woollen (Worsted) socks (22B/55), the latter almost as symbolic of the British Empire as the sun helmet itself!

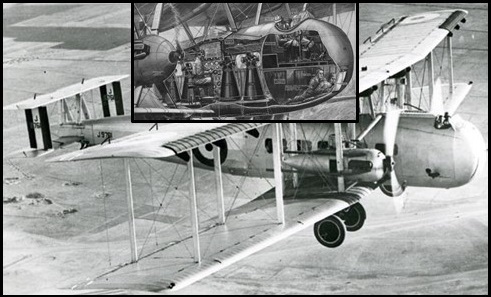

Figure 25. It was not just a fighter-light bomber helmet. Here is shown a ‘Vickers Victoria’ troop carrier, the open side-by-side cockpit (see inset cutaway drawing) led to the cork helmet being required when flying in tropical areas. Between WWI and the mid1930s most RAF heavy bombers and transports had open cockpits, meaning the cork aviation helmet was standard issue to their crews in tropical areas as well as the fighter and light bomber crews usually imagined.

Figure 25. It was not just a fighter-light bomber helmet. Here is shown a ‘Vickers Victoria’ troop carrier, the open side-by-side cockpit (see inset cutaway drawing) led to the cork helmet being required when flying in tropical areas. Between WWI and the mid1930s most RAF heavy bombers and transports had open cockpits, meaning the cork aviation helmet was standard issue to their crews in tropical areas as well as the fighter and light bomber crews usually imagined.

Figure 26. Transport pilots in cork aviation helmets. Left, Vickers troop carrier pilot talks to officials, 1928-29, during the Kabul, Afghanistan, evacuations. Right, crew of another Vickers troop carrier, the pilot is wearing a contrasting coloured puggaree on his helmet; in the plane’s doorway another crew member has his helmet in his hand.

Figure 26. Transport pilots in cork aviation helmets. Left, Vickers troop carrier pilot talks to officials, 1928-29, during the Kabul, Afghanistan, evacuations. Right, crew of another Vickers troop carrier, the pilot is wearing a contrasting coloured puggaree on his helmet; in the plane’s doorway another crew member has his helmet in his hand.

Figure 27. Vickers Vincents flying along the Euphrates, Iraq, 1938. The exposed pilot at front wears a light coloured sun helmet, with darker puggaree, or external goggle strap. The bomb aimer in the relatively protected rear cockpit is free to enter the fuselage and appears to wear a close fitting flying cap. Inset, poor quality image of an 8 Squadron pilot at a crash site of a Blenheim in Aden 1939, he has his earflaps fastened over the top of the helmet.

Figure 27. Vickers Vincents flying along the Euphrates, Iraq, 1938. The exposed pilot at front wears a light coloured sun helmet, with darker puggaree, or external goggle strap. The bomb aimer in the relatively protected rear cockpit is free to enter the fuselage and appears to wear a close fitting flying cap. Inset, poor quality image of an 8 Squadron pilot at a crash site of a Blenheim in Aden 1939, he has his earflaps fastened over the top of the helmet.

Figure 28. WWII, 27th November 1940, a RAF Bristol Blenheim crew take refreshment in North Africa. At centre the cork aviation helmet’s earflaps are fastened over the top of the helmet, two others appear to have removed the earflaps altogether. Although on the books for another year and a half, it was by this time becoming rare. Externally, apart from the width of the front peak, it appears near identical to the WWI 1917 Pattern. In its lifetime the Cork Aviation Helmet was contemporary to at least 4 standard issue RAF caps and helmets, all 4 of which had become obsolete during its life-time.

Figure 28. WWII, 27th November 1940, a RAF Bristol Blenheim crew take refreshment in North Africa. At centre the cork aviation helmet’s earflaps are fastened over the top of the helmet, two others appear to have removed the earflaps altogether. Although on the books for another year and a half, it was by this time becoming rare. Externally, apart from the width of the front peak, it appears near identical to the WWI 1917 Pattern. In its lifetime the Cork Aviation Helmet was contemporary to at least 4 standard issue RAF caps and helmets, all 4 of which had become obsolete during its life-time.

Figure 29. A Vickers Wellesley in Eritrea, in 1941. Only recently given the designation ‘Type A’ the Cork Aviation Helmet was finally replaced as the RAF’s tropical helmet the following year, by the cotton Type D.

Figure 29. A Vickers Wellesley in Eritrea, in 1941. Only recently given the designation ‘Type A’ the Cork Aviation Helmet was finally replaced as the RAF’s tropical helmet the following year, by the cotton Type D.

Design History

Although it is often assumed that the ‘cork aviation helmet’ was a preexisting sun helmet design to which earflaps had simply been added, a study of 1917 and earlier images and advertising of both sun and polo helmets, does not appear to show this exact model existing elsewhere. This could mean the shell was designed from scratch when the ‘HQ Royal Flying Corps Middle East’ requested a sun helmet for aviators in, or before 1917. The unusual features of the style such as a lack of top ventilator and button, and the narrow brim were probably concessions to aerodynamics and cockpit/riggingng-wire space restrictions. The resulting compactness led to it superficially resembling some styles of ‘polo’ helmet, but this was probably coincidental. The style remained fundamentally the same from 1917 to its final years in the early 1940s. New production begun around 1927-30, with an extended front peak, simpler headband attachment method with earflaps attached to the liner and details of the cut of the cloth covering changed. During this period, it was general issue to all classes of RAF and semi-official, and expedition aviators throughout the tropical parts of the British Empire; Dominions; Protectorates and Mandated Territories.

Figure 30. The Cork Aviation Helmet was ‘de-rigueur’ when celebrity aviators were passing through tropical areas. Here (L to R), record breaking Amy Johnson 1930, (solo UK to Australia); Amy Johnson, 1932 (solo London to Cape Town); Lord Clydesdale, 1933 (first Everest over flight) and Jean Batten, 1936 (solo UK to New Zealand) all used the type. Second Left, Amy Johnson is posed for press photographers in overcast London, holding a cork aviation helmet; and Lord Clydesdale walks out to his aircraft at Heston Aerodrome, UK, to start the expedition to overfly the ‘Roof of the World’. The prominently displayed helmets were powerful symbols of exotic adventure.

Figure 30. The Cork Aviation Helmet was ‘de-rigueur’ when celebrity aviators were passing through tropical areas. Here (L to R), record breaking Amy Johnson 1930, (solo UK to Australia); Amy Johnson, 1932 (solo London to Cape Town); Lord Clydesdale, 1933 (first Everest over flight) and Jean Batten, 1936 (solo UK to New Zealand) all used the type. Second Left, Amy Johnson is posed for press photographers in overcast London, holding a cork aviation helmet; and Lord Clydesdale walks out to his aircraft at Heston Aerodrome, UK, to start the expedition to overfly the ‘Roof of the World’. The prominently displayed helmets were powerful symbols of exotic adventure.

The cork aviation helmet was used in tropical regions for 26 years until finally replaced in 1942 (IWM date) by the Type D Flying Helmet (22c/581-584), (see Fig. 31). This new tropical helmet was a typical close fitting cap type, made of khaki cotton with a moon shaped neck flap for sun-protection and, importantly, had standard ‘modern’ snap attachments for an oxygen/microphone mask, molded rubber housings for earphones and external leather straps for goggle retention. These changes marked not only the phasing out of open cockpit aircraft, but also the ubiquitous and harmonized communications systems and higher altitude operations that were becoming standard.

Figure 31. The RAF ‘tropical flying helmets’. The ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’ (1917-1942), called the ‘Type A’ only from 1940 to 1942, and its eventual replacement the ‘Type D’ (1942-mid 1950s).

Figure 31. The RAF ‘tropical flying helmets’. The ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’ (1917-1942), called the ‘Type A’ only from 1940 to 1942, and its eventual replacement the ‘Type D’ (1942-mid 1950s).

Contemporaries

The ‘cork aviation helmet’ was a contemporary to – initially 22C/5 the ‘Fur-lined cap (‘Summer’ in F.S. 133) and conversions thereof during late WWI and the 1920s. Also until 1924 the ‘cork aviation helmet’ 22C/13 appeared on lists directly after 22C/12 ‘Helmet, Aviation’, a ‘helmet’ whose identity has caused some confusion, but was almost certainly the second Pattern Warren Safety helmet. Fourteen years after it first appearance the Cork Aviation Helmet was being issued alongside the ‘1930 Pattern’ (22C/51) until the mid-30s. From 1935 it was a contemporary of the ‘Type-B’ 22C/65 helmet. As mentioned when WWII started the Cork Aviation Helmet received the additional sequence 22C/274-284, denoting the eleven sizes then available and retrospectively given the new designation ‘Type-A’. It was followed in the updated lists immediately by the ‘Type-B’, which received 22C/285-288; denoting its four size range. By late 1941-early 1942 the Cork Aviation Helmet was seldom used for actual flying, but would still have been on the books when the Type-C was adopted.

Figure 32. The three pieces of flying headwear included in the first officially published RAF equipment list F.S. 133, May, 1920. 22C/5 ‘Caps, Fur-Lined’, 22C/12 ‘Helmets, Aviation’ and 22c/13 ‘Helmets, Cork, Aviation’.

Figure 32. The three pieces of flying headwear included in the first officially published RAF equipment list F.S. 133, May, 1920. 22C/5 ‘Caps, Fur-Lined’, 22C/12 ‘Helmets, Aviation’ and 22c/13 ‘Helmets, Cork, Aviation’.

Figure 33. Inter-War and early WWII the cork aviation helmet was contemporary to several others. Left, the Fur-Lined Cap (22C/5) continued in use until ~1930, it provided the basis for many adaptations, here is an early modification (1917), for high altitude work, it has no peak, no wind baffle rolls and has buckles behind the earflaps for attachment of a fur-lined bib, or ‘throat warmer’. Many modifications of 22C/5’s occurred during late WWI and the 1920s, but these remained modifications of 22C/5 and no new 22C number was issued for them. Second left, the Cork Aviation Helmet, 22C/13, remained in use in the tropics, 1917-1942. Second right, ‘1930 Pattern’ 22C/51, trialled in the late 1920s, with an RAE report ‘New Type Flying Cap’ (National Archive – AVIA 18/39) produced in 1928, adopted around 1930 and issued until the mid-1930s. When declared obsolescent these helmets were transferred to RAF flight school ‘kit bins’ where they were worn to destruction by wartime trainees, hence its rarity today. Right, the ‘Type-B’ 22C/65, a development of the ‘1930 Pattern’, shortened nape, a buckle adjusted slit in back (rather than elasticated nape in the 1930 Pattern) and ‘Bennet buckles’. Like the 1930 Pattern these were issued without earphone pockets, as here, but most had them attached by base tailors. It was given the extra sequence 22C/285-288 (with ear-pockets), 289-293 (without ear-pockets) in ~1940 denoting the size ranges.

Figure 33. Inter-War and early WWII the cork aviation helmet was contemporary to several others. Left, the Fur-Lined Cap (22C/5) continued in use until ~1930, it provided the basis for many adaptations, here is an early modification (1917), for high altitude work, it has no peak, no wind baffle rolls and has buckles behind the earflaps for attachment of a fur-lined bib, or ‘throat warmer’. Many modifications of 22C/5’s occurred during late WWI and the 1920s, but these remained modifications of 22C/5 and no new 22C number was issued for them. Second left, the Cork Aviation Helmet, 22C/13, remained in use in the tropics, 1917-1942. Second right, ‘1930 Pattern’ 22C/51, trialled in the late 1920s, with an RAE report ‘New Type Flying Cap’ (National Archive – AVIA 18/39) produced in 1928, adopted around 1930 and issued until the mid-1930s. When declared obsolescent these helmets were transferred to RAF flight school ‘kit bins’ where they were worn to destruction by wartime trainees, hence its rarity today. Right, the ‘Type-B’ 22C/65, a development of the ‘1930 Pattern’, shortened nape, a buckle adjusted slit in back (rather than elasticated nape in the 1930 Pattern) and ‘Bennet buckles’. Like the 1930 Pattern these were issued without earphone pockets, as here, but most had them attached by base tailors. It was given the extra sequence 22C/285-288 (with ear-pockets), 289-293 (without ear-pockets) in ~1940 denoting the size ranges.

Descendants

If the 1917 shell design was indeed unique it may indicate that the better known 1930s/WWII/1950s South African ‘polo’ helmet was in fact an adaption of the more than decade old RFC/RAF cork flying helmet. The term ‘polo’ helmet in this case is a descriptive term, as it resembled a polo helmet, but was probably never used as such. It has been stated (Bates & Suciu, 2009) that the South African Air Force (SAAF) were the first South Africans to use the style domestically in 1930, it probably being poplar because of its original design as a compact flying helmet. The rest of the South African military adopted the style beginning in 1934 due to its compact form being ideal for bush work. The South African Army version had earflaps omitted for terrestrial use and tended to have a button covered top vent for pedestrian ventilation. These were initially produced by contractors in the UK, but local SA manufacture soon dominated (Peter Suciu, 2015). The standard aviation type was also produced locally for the SAAF through the 1930s and into WWII; the SA Army version’s top ventilator/button was sometimes included on the domestic flying model. The terrestrial type was used in South Africa until at least the late 1950s; so one family branch of the 1917 RFC design can claim to take the lineage to around 40 years.

Figure 34. Dominion examples of the Cork Aviation Helmet. Left, a standard British made (Owen’s Comfortlit) example issued by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF)(a). CenterLeft, an example issued to a Canadian in the RAF 1940, described as ‘Summer Dress’ (Canadian War Museum (b)). Center Right, a standard pattern Cork Aviation Helmet, but in blue, has South African badge and flash, but was British made(c). Right, A South African made Cork Aviation Helmet, using the South African Army shell with top vent.

Figure 34. Dominion examples of the Cork Aviation Helmet. Left, a standard British made (Owen’s Comfortlit) example issued by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF)(a). CenterLeft, an example issued to a Canadian in the RAF 1940, described as ‘Summer Dress’ (Canadian War Museum (b)). Center Right, a standard pattern Cork Aviation Helmet, but in blue, has South African badge and flash, but was British made(c). Right, A South African made Cork Aviation Helmet, using the South African Army shell with top vent.

Figure 35. Post 1934 South African Army sun helmets; due to their very close similarity and the time line of appearance these are here assumed to be an adaption of the 1917-1942 RFC/RAF ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’. By convention, these are now termed the ‘South African ‘polo’ helmet’. Peter Suciu (2015) has pieced together much of the history of this type. Left, a standard SA military model, these were produced for South Africa by contractors in the UK, but local SA manufacture soon dominated. Center, with the winds of war SA realized that general mobilization might be called for and looked overseas for contractors to increase stocks, as the UK was busy reequipping itself; they chose the Dutch firm, ‘JP. De Mol, Breda’. De Mol had substantially fulfilled the contract, but not shipped, when Germany invaded the neutral country 10 May 1940. The Germans commandeered the order and outfitted several units with them who were deploying to North Africa. Right, perhaps to replace the purloined Dutch made SA helmets it seems substantial contracts were given to the British companies Vero & Everett Ltd and Failsworth Hats Ltd. These late UK made examples appeared to go back to the original Cork Aviation Helmet design, as they left off the SA modification of a top vent, and have goggle retaining loops. Probably due to wartime exigencies, they were produced in pressed felt or felt/cork lamination. Many of these models are found dated to 1941 and 1942. Although some did get to South African forces and were used, many appear to have never been issued, perhaps due to the War in the West moving on from tropical areas.(However, their origin may be as aborted RAF Type A flying helmets? (see next figure).

Figure 35. Post 1934 South African Army sun helmets; due to their very close similarity and the time line of appearance these are here assumed to be an adaption of the 1917-1942 RFC/RAF ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’. By convention, these are now termed the ‘South African ‘polo’ helmet’. Peter Suciu (2015) has pieced together much of the history of this type. Left, a standard SA military model, these were produced for South Africa by contractors in the UK, but local SA manufacture soon dominated. Center, with the winds of war SA realized that general mobilization might be called for and looked overseas for contractors to increase stocks, as the UK was busy reequipping itself; they chose the Dutch firm, ‘JP. De Mol, Breda’. De Mol had substantially fulfilled the contract, but not shipped, when Germany invaded the neutral country 10 May 1940. The Germans commandeered the order and outfitted several units with them who were deploying to North Africa. Right, perhaps to replace the purloined Dutch made SA helmets it seems substantial contracts were given to the British companies Vero & Everett Ltd and Failsworth Hats Ltd. These late UK made examples appeared to go back to the original Cork Aviation Helmet design, as they left off the SA modification of a top vent, and have goggle retaining loops. Probably due to wartime exigencies, they were produced in pressed felt or felt/cork lamination. Many of these models are found dated to 1941 and 1942. Although some did get to South African forces and were used, many appear to have never been issued, perhaps due to the War in the West moving on from tropical areas.(However, their origin may be as aborted RAF Type A flying helmets? (see next figure).

Figure 36. The 1941-42 ‘felt’ sun helmets by Vero & Everett Ltd and Failsworth Hats Ltd. The ~1940 edition of ‘Air Publication 1086’ gave the RAF Cork Aviation Helmet a set of eleven new numbers, making it clear that it was expected to play a role in the unfolding conflict. It seems probable that contracts were then given to Vero & Everett Ltd and Failsworth Hats Ltd, to supply the war-time RAF ‘Type A’ helmet. Before the contract could be fulfilled, however, it appears the development and issue of the ‘Type D’ tropical helmet made the type obsolete. Above a pair of the ‘felt’ sun helmets; it can be seen that apart from the felt shell material, they are identical to pre-War ‘cork aviation helmets’, including the laced in liner and goggle retaining loop. It seems upon their obsolescence as aviation helmets, they had chinstrap hooks added and were taken on by the War Department (receiving a broad arrow and WD stamp), rather than the Air Ministry (A.M. stamp) and disposed of in places where they might be useful. As mentioned above some seem to have been picked up by the South African military, and some others seem to have made it to Canada and elsewhere, where many became surplus stock and were sold off to the public post-war, hence they are often in near pristine condition. No felt version ever seems to have been completed as an RAF ‘Type A’ flying helmet.

Conclusions

Being issued to aviators in the non-domestic areas, known variously as the ‘Middle East’ or ‘East of Suez’ the helmet has received scant attention in general RAF equipment histories. The Cork Aviation Helmet was demonstrably in use in the last year of WWI, and became a very important part of tropical kit in the RAF’s post-war mandated role of ‘Colonial Policing’. As such it was the helmet worn during many of the RAF’s interwar belligerent actions. It was used by generations of RFC/RAF and Commonwealth aviators over a vast geographic range. Pioneers, record breakers and explores recognized the designs practicality and symbolism and readily wore them when appropriate.

Contrary to conventional wisdom the ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’ was probably not based on a pre-existing sun/polo helmet, but was a totally new model of sun helmet designed to be compact for the particular needs of sun protection in open cockpits. The basic 1917 Pattern was used in tropical areas until 1942, with a few modifications. Early production seems to have been by Hobson & Sons, it was a simple thick cork dome with a 4 panel light canvas cover to which separate front and rear peaks were attached. The front peak was only about a ~1/2 inch wide, but the rear peak was 3-4 inches broad, cork spacers between the shell and liner formed a typical sun helmet ventilation gap. The Pattern seems to have been revised by at least mid-1919, with the brim appearing now to be part of the cork shell forming a one piece encircling brim with the front peak noticeably enlarged from the 1917 version. The 1917 Pattern and those whith the early brim revision were used up to 1927, and were possibly old war-time stock. Production seems to have recommenced after 1927 manufactured mainly by Charles Owen & Co, with their laced in liner ‘Royal Letters Patent No. 207475’, a couple of other manufactures can be found, all however, using the ‘Owen’ type liner. This late 1920s revised Pattern was the result of the 1926-1927 RAE reports, the old Patterns being tested then to see if the type should be continued, as new equipment was at that time being considered for the first time since WWI. The existing 1917 Pattern and its revised versions were found to be ‘satisfactory’ and, with some further slight revisions, production recommenced.

Suggested Revision Dates: –

1917 – Original Pattern

1918-1919? – Brim revised, becomes part of the cork shell and encircles the whole helmet, with slight increase in front peak width.

1927-30 – Fixing for the earflaps moved to sweatband rather than shell, Owens’ patent laced in liner introduced to all.

1941-42 – Felt or felt/cork laminated shells introduced, but type made obsolete before these were issued. Finished as normal sun helmets

Surviving examples are overwhelmingly khaki; a vary variable khaki from pale green to pale beige, even off white; sometimes shell, earflaps and puggaree are all slightly different, it is not known how much of this is variability in manufacture, or variable environmental bleaching or staining. However, factory made blue examples exist, as do what appear to be period painted specimens. Period monochrome images do indeed appear to show many examples that have tonal values differing from that expected from standard khaki. Transport crew especially appear to have sometimes had contrasting coloured puggarees and shell, perhaps to look less military for the benefit of civilian passengers.

Its original designation was ‘Helmet, Cork Aviation, RFC Pattern 1917’ (to distinguish it from RNAS types), but after the formation of the RAF in April 1918, it became the RAF ‘Helmet, Cork Aviation’ or normally ‘Cork Aviation Helmet’ and this seems to be the term which appeared in official documents throughout its life time. The alphanumeric terms often quoted seem to have been for administration purposes only.

It was variously known as: –

1917-1918, Cork Aviation Helmet, RFC Pattern 1917.

1918-1942, RAF, Cork Aviation Helmet. (Sometimes ‘summer wear’ or ‘summer dress’)

1920-1942 22C/13

1921-1924 Code word ‘SDYBI’

~1940-1942 22C/274-284

~1940-1942 Type-A

At the start of WWII it received a new series of 22C numbers 274 to 284 related to sizes, indicating it was expected to play a part in the unfolding conflict. As the war developed in North Africa, however, the Cork Aviation Helmet quickly became less popular, due not only to enclosed cockpits, but also due to its lack of fittings for O2/microphone masks and its primitive receiver pockets. This lead to the Type-B and Type-C soft ‘helmets’ becoming more practical, even in the tropics. The Type-D Tropical Flying Helmet officially superseded the Cork Aviation Helmet in 1942, after 26 years of service.

The term ‘East of Malta’ has been applied uniquely to this helmet but does not appear in accessible official or colloquial military parlance elsewhere, so it may possibly be an early author’s or archivist’s personal descriptive term or be of some other lost post war informal origin. The author would be interested in finding the earliest reference to the term ‘East of Malta’ associated with this helmet.

Due to their remarkable similarity it seems the 1930s South African military’s ‘polo’ helmet was an adaption of this relatively old aviation design. This theory adds significant convolutions to the South African ‘polo’ helmet’s already complex story (Peter Suciu, 2015).

Although these helmets were issued to large numbers of aviators over a vast geographic range for a quarter of a century, examples today are very rare. This may be because it was a smart and practical little sun helmet, so when obsolete they were eagerly sought out by individuals who removed the earflaps (simply by unlacing and re-lacing the liner) and used then for everyday wear until worn out, they were then discarded in tropical areas; with few making it home to collectors shelves.

The final 1941-42 production-run by Vero & Everett Ltd and Failsworth Hats Ltd, was interrupted by the development and issue of the Type-D Tropical Helmet. These felt bodied shells were never completed as aviation helmets and together with some early 1940s cork versions were finished as basic sun helmets. These became unwanted orphans in the hands of the War Department, a few were used by the South African Army, but many more were sold off as surplus stock post war.

Steve Saunders

April, 2020

17th July 1922, from left, Macmillan, Blake and Malins at RAF Shaibah, Iraq, during their ill-fated circumnavigation of the world (https://www.historynet.com/foredoomed-to-failure-an-attempt-to-fly-around-the-world.htm). Macmillan wears an ‘old’ ‘RFC 1917 Pattern, Cork Aviation Helmet’ and Malins the 1919? revised ‘RAF Cork Aviation Helmet’ with complete brim. Blake’s helmet, at center, appears to be a modified ‘Bombay Bowler’ with steeper brim. They had been given these sun helmets, as well as maps and an escort by the worried staff at RAF Aboukir, Palestine before they crossed the Syrian Desert.

Due to their rarity (only 2 close-up photos in existence?), an enlarged view of Macmillan’s ‘RFC 1917 Pattern, Cork Aviation Helmet’.

Acknowledgments

As always thanks go to Stuart Bates and Peter Suciu for their encouragement and providing an outlet for such obscure research. Being such a run of the mill, everyday item much original source material has been disposed of or was never recorded, however, scattered among museums, libraries, archives and private photograph albums is factual contemporary material relevant to the helmets development and usage history. I thank the staff of The Imperial War Museum, London; The Imperial War Museum, Duxford (William Cameron); The British Library (Social Sciences Enquires and Asian and African Studies Enquires); The National Archives, Kew and the Royal Air Force Museum, London, (especially Ewen Cameron and Andrew Dennis) for their help in tracking down various obscure primary documents and items.

References

‘Helmet, Cork Aviation RFC Pattern 1917’. Catalogue number item UNI 177. Imperial War Museum collections,

‘Art. IWM ART 4617’, Imperial War Museum collections

‘Provisional Vocabulary of Stores for the Royal Air Force’, Field Service (F.S.) 133 (post publication corrected by ink stamp to ‘Air Publication 133’), May 1920. (RAF Museum)

‘Priced Vocabulary of Royal Air Force Equipment and Meteorological Stores’, Air Publication 809; 1921 Edition. (National Archives)

‘A Priced Vocabulary of Royal Air Force Equipment’, Air Publication 1086, 1 Oct. 1924. (British Library)

‘A Priced Vocabulary of Royal Air Force Equipment’, Air Publication 1086, 1 Oct. 1927. (British Library)

‘Index to Air Ministry Weekly Orders. 20th March, 1918, to 31st December, 1930. With List of Cancelled Orders’. In – a volume of Air Ministry Weekly Orders for 1930, held by the British Library, Indian Office Records (IOR/L/17/10/323).

‘Fur-Lined Caps and Cork Aviation Helmets—Alteration to prevent Loss of Goggles.’ Air Ministry Weekly Orders 583222/1925. 568. (British Library)

‘Helmets, cork, aviation— Alteration to prevent Loss of Goggles.’ Air Ministry Weekly Orders 602/1926. (small amendment to 568). (RAF Museum)

‘Report on cork aviation helmet’. 18th Oct.1926. Royal Aircraft Establishment. Report No. K.2186. (National Archives)

‘Report on cork aviation helmet’. 30thSep.1927. Royal Aircraft Establishment. Report No. K.2278. (National Archives)

‘New Type Flying Cap’. 1928, Royal Aircraft Establishment. Report. (National Archive – AVIA 18/39)

Images in the Figure 1 and Figure 12 are from Brian Johannesson’s collection, https://www.rareaviationphotos.com/index.htm)

Images in Figure 35 are from :-

- Victorian Collections (http://victoriancollections.net.au)

- Canadian War Museum (http://www.warmuseum.ca)

- The Historic Flying Clothing Company. (http://www.historicflyingclothing.com)

Cormack and Cormck (2001). ‘British Air Forces 1914-18’. Osprey Books.

Stuart Bates and Peter Suciu (2009). ‘The Wolseley Helmet in Pictures, From Omdurman to El Alamein’. PSB Publishing.

O’Hara (2005). ‘The Early Days’. Royal Air Force Historical Society, Journal 35 (Seminar – Supply – An Air Power Enabler).

Rood (2014). ‘A Brief History of Flying Clothing’. Journal of Aeronautical History. Paper No. 2014/01

Stone (2017). ‘Sustaining Air Power: Royal Air Force Logistics since 1918’. Fonthill Media

Peter Suciu (2015) ‘The Dutch-South African Helmet Connection’. (http:/www.militarysunhelmets.com/2015/the-dutch-south-african-helmet-connection)

Peter Suciu with others. –Wehrmacht-Awards.com –‘Sun Helmet Discussion for DAK Historians’

Mick J Prodger (1995) ‘Vintage Flying Helmets, Aviation Headgear Before The Jet Age’. Schiffer Publishing Ltd.