This is a special study of Japanese tropical helmets by Nick Komiya, and is presented in four parts.

1887-1911 Colonial Predecessors of the Army Sun Helmet

Initially a trademark of the British and French colonial look, the wearing of pith helmets spread worldwide from the late 19th to the early 20th centuries. However, despite of this worldwide fad, Japan was slow in coming to see any need for such gear. That was because being a late comer to the game of Imperialism, Japan did not hold any tropical colonies.

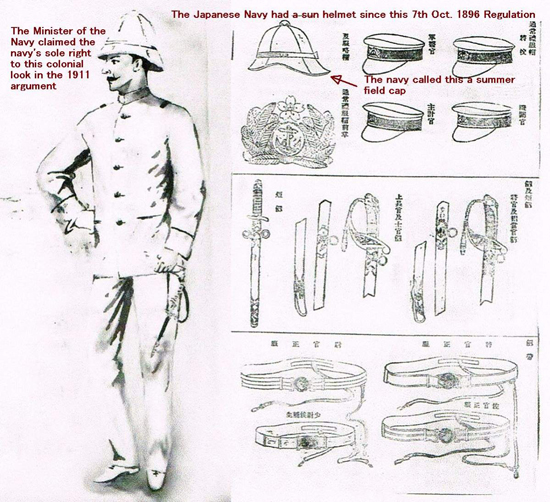

But even so, the well-travelled Japanese Navy must have felt obliged to match the colonial style dress code when making port calls at tropical colonies of the European empires. Thus the Imperial Japanese Navy introduced a sun helmet already in 1887, nearly 40 years ahead of the army.

Introducing sun helmets for wear within its own territory as a colonial necessity was a thought that occurred to Japan only after gaining Taiwan as territory, as a result of winning the first Sino-Japanese War of 1894/95. Taiwan has the Tropic of Cancer bisecting the island roughly at midpoint, making Northern Taiwan part of the Subtropics, and Southern Taiwan the Tropics. Head Quarters for the Japanese government outpost for Taiwan was set up in Taipei within the subtropics zone at the north end of the island, but when they made a request to establish uniforms for the Japanese workers and police there, their request included sun helmets as a matter of course.

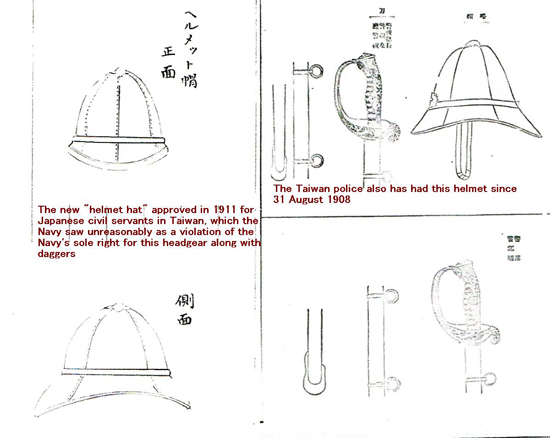

However, documents dated 16th March 1911, establishing these uniforms for the Taiwan bureaucracy were also accompanied by documents of protest from the Navy, which was strongly opposed to the uniform designs. They were throwing a tantrum claiming that a civil servant in the employ of the Japanese Governor-General of Taiwan, wearing his sun helmet, white uniform and dagger would look identical to a navy man.

You could almost hear the sighs from the Prime Minister and others, as they patiently explained to the Minister of the Navy that the civil servant uniforms for Taiwan were not set up with shoulder boards, but sleeve insignia instead, so they could not be mistaken for navy. The Navy’s protest was overridden, but the fact that even documents signed by the Emperor in sanctioning the new uniforms saw it necessary to address the Navy’s argument point for point shows how jealously the navy tried to protect its own trademarks. They particularly resented the idea of non-military personnel wearing daggers, though they said they would let the sun helmet go, if the shape were suitably changed, not to resemble a navy one.

1915-16 “Round 1” of Army Field Tests in Taiwan, the German War Booty Sun Helmets

It was WW1 that suddenly changed Japan’s fortunes in the tropics. The former German islands in the Pacific such as Palau, Micronesia, Marshall Islands, surrendered to Japan, and Japan would now govern the area as the South Pacific Mandate. As the South Pacific suddenly became a vested interest for Japan, it followed that Japan also needed to defend these possessions.

Thus in 1914, the army decided it was finally time to have tropical uniforms.

As a happy coincidence, it was not only Pacific islands that Japan won, but also large stocks of pith helmets came with this victory over Germany.

As the army was starting to consider a similar design, it decided to make use of this windfall to gauge field acceptance for such new headgear by issuing large numbers of these helmets to its troops in Taiwan.

Back in 1907, the army had established two Taiwanese Infantry Regiments. The first regiment covered the mid to northern part of Taiwan, and the second regiment covered the south, so issuing them the German helmets allowed field tests in both subtropical and tropical climates at the same time. Thus in early August of 1915, 2,980 German Sun Helmets were shipped to Taiwan from the Hiroshima Depot.

The troops in Taiwan were instructed to add Army visor cap stars and chin straps to the German helmets (The army referred to these as ヘルメット形夏帽 ”helmet type summer hats”). They were to wear them for two summers of 1915/16 and report on 7 points.

(1) Handiness, (2) Effectiveness in preventing sun stroke, (3) Suitability as a summer hat, (4) Ease of Repair, (5) Resistance to rain, (6) Storage implications, (7) Improvement ideas based on field trial.

The two Infantry Regiments were allocated 1,085 pieces each and the rest went to two Artillery Battalions (260 each) and two Mountain Gun Companies (145 each).

The final verdict from Taiwan, dated 17th January 1917, found the helmet cumbersome to deal with in passing through thick growth and in combat action in comparison to a visor cap, but appreciated its protection against direct sunlight coupled with good internal air ventilation to prevent heat strokes.

They also felt the helmet had good water repellency, but it did get uncomfortably heavy after prolonged exposure to rain. Repair seemed to be somewhat trickier than a visor cap, but within reason.

All in all, they felt that it was a headgear worth having for summer, if some improvements could be made.

They had 6 improvement suggestions. (1) Weight reduction (2) Lower dome profile (3) Flatter angle for the front visor and increased visor size (4) Smaller rear visor or a collapsible rear visor like the neck guard on Samurai helmets, not to interfere with wearing of backpacks and hoods (5) softer leather sweat band to prevent headaches (6) improved water repellency.

1916-1917 “Round 2” First IJA Prototype Test in Central China

Overlapping the last year of German helmet tests in Taiwan, in the spring of 1916, the Army also decided to run a field test of its own prototype design in subtropical Central China.

Japan’s continued winning streak against the large empires of China, Russia and Germany in close succession became an inspiration to many independence movements in Asia, and China’s Qing Dynasty was toppled in 1912 by such a domino effect of the times, the Xinhai Revolution. As many must remember from the film, “The Last Emperor”, the Japanese were quick to see opportunities in this quickly developing vacuum in China and must have anticipated that the next theater for the army would be the Chinese mainland. It must have been this anticipation of impending military action there that made the army shift “Round 2” of the sun helmet tests to China from Taiwan.

Between January 1912 and July 1927, Japan had an expeditionary force of 7,000 men stationed around Hankou 漢口 (present day Wuhan) under the pretense of protecting its own citizens there. It was these troops that got the homework of testing of the army’s sun helmet and tropical shirt prototypes during the summers of 1916 and 1917. They received delivery of 700 sun helmets.

The Army still did not call them 防暑帽 (Anti-heat hats) as they would in WW2, but now called themヘルメット帽 (helmet hats). In English, there is also the commonly used word “hard hat” for modern work helmets, so the Japanese term is not actually as off as it might sound at first.

By this time, they already had some feedback from the first summer of testing the German helmets in Taiwan, so though no documents clearly describe what this prototype looked like, it seemed to address already some of the criticism mentioned above in the Taiwan report.

Of particular interest is that the rear visor was designed so it could be flipped up, not to get into conflict with the shouldered rifle or the back pack with coat strapped on top or when firing in a prone position. It seemed to have a black lacquered front visor, too. Two alternative chin straps were provided, one being a stiff type like the visor cap strap and another soft type. The body of the helmet was made from woven palm fibers (棕櫚). The top vent seemed to have a flower-shaped lid.

These helmets were delivered to the troops by end of April 1916 and they were to wear them for two summers and report each year on 9 main points.

They were; (1) degree of heat protection provided, (2) any restrictions to firing rifles in various stances, (3) implications of exposure to rain, (4) wear comfort, (5) ease of damage repair, (6) ease of storage, (7) suitability of chin strap choice (8) conspicuousness to enemy eyes, (9) any improvement suggestions gained from testing and comparison with standard visor cap.

Strictly for testing in heat, Taiwan would have made more sense, because though Wuhan was normally known for its murderously hot summers, it was in the subtropics zone, not quite the tropics and this particular summer was much milder than usual. The report from China dated 13th November 1916 said humidity, that commonly rose above 90% to make it insufferable during summers, only hit that mark for 8 days in the 3 months of June to August that year.

Also, though temperatures of more than 30 degrees centigrade should have been common, the average summer heat that year was only 27.8 degrees.

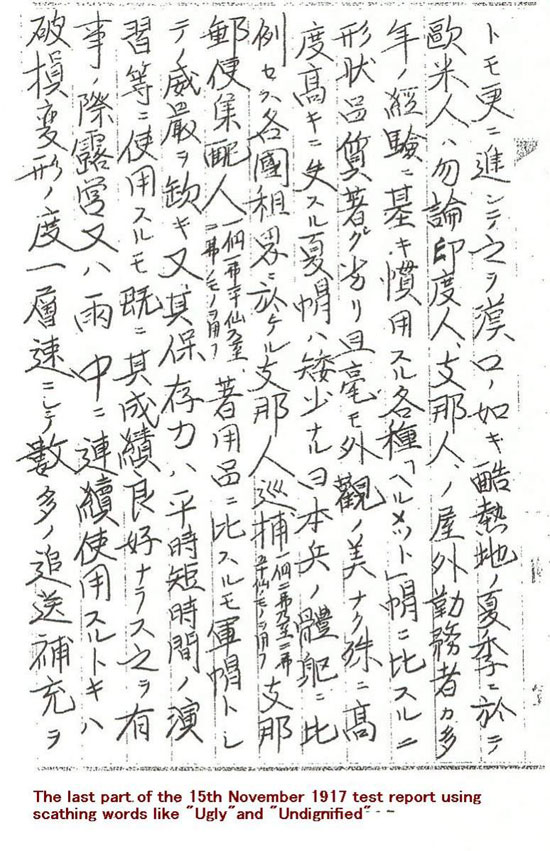

Comments from the troops started out somewhat positive by lauding the good protection it provided against the heat, but they were only imparting the good news before the really bad, as it became quite a scathing criticism towards the end, when the final verdict came from China after the second summer dated 15th November 1917.

The executive summary said “Though it is not unsuitable for military use, many improvements are still needed.” The heat alleviating properties were consistently well received, but even with the flip-up rear visor, problems persisted in shooting in the prone position and with snagging on the pack when moving the head.

They even suggested the flip-up structure should be a spring-loaded one to keep the visor properly held up, all the way up to a 90–degree angle. They also said the front visor should be made to flip up, and instead of glossy black lacquer, plain cloth or at least a matte finish was suggested.

Water repellency was generally good, but when it did eventually get soaked through, the woven palm fibers created a warped and lumpy surface when dried up, so they suggested using light cork or gourd sponge instead as shell material.

The glued-in flax lining under the sweatband was quite stiff, so combined with the weight of the helmet (in comparison to the visor cap) some started to get headaches only 1 hour after putting the helmet on.

Thus height and weight reduction of the overall design was requested as an absolute must. Repair work by the soldier in the field was rated as a totally hopeless proposition. The flower shaped vent lid on top often got ripped off, because of poor soldering to the fixing screw.

The lacquered leather sweatband soon lost all its finish after absorbing sweat and did not last even one summer, so the material used in visor caps was suggested. In terms of concealment from the enemy, the troops did seem to be quite content.

All this still sounded like constructive criticism, while they patiently addressed the obligatory check items one by one, but they had saved the worst for last.

The report ended by saying “ In a region of extreme summer heat like Wuhan, not only Europeans, but also the Indians, Chinese and others who need to work outdoors have devised various types of “helmet hats” out of long experience. In comparison to those native models, the prototypes in question are far inferior in both quality and design. The design is outright ugly and the exaggeratedly high dome of the sun helmet on a tiny Japanese soldier looks totally out of balance and ridiculous. The helmets worn by the Chinese constables and mailmen in the international concession areas are far more dignified in comparison. Even in short maneuvers, durability has proven to be far from satisfactory, so continuous exposure to the elements would surely cause them to fall apart and lead to a flood of replacement demands from the field. A serious attempt should be made to collect and study headgear already out there.”